“No experienced writer would ever think of using Massachusetts in a song title, and yet this state is just as picturesque and romantic as New Hampshire.”-- E.M. Wickes, Writing the Popular Song (1916)

As a follow-up to my previous essay,

I've started reading Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the

Invention of the Blues by Elijah Wald – another of the recent

group of revisionist blues histories. Wald does a much better job, as

far as I can see, of providing a proper historical and musical

context for the “invention” of the blues. Along the way, Wald

makes a fairly brief aside that struck me as interesting: he

contrasts (pp. 31-32) the marketing of music in the 1920s to the

African-American and country markets. He notes that African-American

records were marketed as “race records”, and were sold as

up-to-date music, while country records were marketed as “Old-Time

Music.” Wald then proceeds to draw a line of nostalgia from 1920s “old time”

music through country-and-western history up to “new country”

stars today.

Wald oversimplifies the contrast between race and old-time records – there are definite cases in the 1920s when blues recordings were marketed as old-time music (for instance, see the examples gathered by Richard Middleton in Voicing the Popular: On the Subjects of Popular Music). But, generally speaking, in the 1920s Old-Time Music referred to white “hillbilly” or country music. And on the broader point, I think Wald is perceptive; but I would like to propose an additional origin for the nostalgic element in new country music: the Tin Pan Alley pop song type known as the “nostalgia” song (or home song, or mother song, or rustic ballad).

Wald oversimplifies the contrast between race and old-time records – there are definite cases in the 1920s when blues recordings were marketed as old-time music (for instance, see the examples gathered by Richard Middleton in Voicing the Popular: On the Subjects of Popular Music). But, generally speaking, in the 1920s Old-Time Music referred to white “hillbilly” or country music. And on the broader point, I think Wald is perceptive; but I would like to propose an additional origin for the nostalgic element in new country music: the Tin Pan Alley pop song type known as the “nostalgia” song (or home song, or mother song, or rustic ballad).

Oddly, while this type seems to be

well-known to music historians and musicologists, it is rarely

discussed in detail. Peter Muir in Long Lost Blues gives a

brief presentation that is at least a good starting point: the

nostalgia pop song has a long history, traceable to the mid-19th century with songs like Stephen Foster's “My Old Kentucky Home”

and, a little later, “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” by James

Bland. The song type was especially popular in the early decades of

the 20th century, by which point the songwriting industry

of “Tin Pan Alley” was well-established. These songs are often

referred to as “Southland” or “Down South” songs (especially in the more detailed treatments; see Earl F. Bargainnier's thematic

analysis in “Tin Pan Alley and Dixie: The South in Popular Song,”

which was helpful in the following discussion). However, while the

songs generally display nostalgia for the South, the object of

longing can also be elsewhere, especially in the Midwest – for

example, “(Back Home Again In) Indiana.” More than even the

South, they were generally nostalgic for rural life, although a song

like “Dallas Blues” might fit the basic category.

One way to approach this song type,

which I would like to try here, is thematic analysis. Studying the

lyrics of a selection of nostalgia songs – and it must be a

selection, as the corpus of these songs is so vast – can help us

identify common themes. And, as it turns out, even a survey of a

small sample of these songs reveals a series of recurring motifs or

themes. These include, but are not limited to

These songs contain a set of stock images – generic images that are barely elaborated in the lyrics. They are so cliched, so stereotyped, that it seems as if pretty much anyone could write them. And pretty much anyone did. There are so

- people as welcoming or kind: for instance, “Arkansas Blues,” “Tishomingo Blues”

- moon(light): (“Back Home Again In) Indiana,” “Wabash Blues,” “Georgia On My Mind,” “Tishomingo Blues,” “When It's Sleepy Time Down South,” “By The Old Ohio Shore,” “Beautiful Ohio”

- trees: “(Back Home Again In) Indiana,” “Wabash Blues,” “Georgia on My Mind,” “Tishomingo Blues,” “When It's Sleepy Time Down South,” “By The Old Ohio Shore.” The trees often stereotypical for the state or region: e.g., the pines of Georgia in “Georgia on My Mind”; sycamores of “Indiana” and “Wabash Blues.”

- (log) cabin: “Arkansas Blues,” “I've Got The Blue Ridge Blues”

- a body of water, usually a river: “(Back Home Again In) Indiana,” “Beautiful Ohio,” “By The Old Ohio Shore.” The latter two songs also share the motif of a canoe; here we have a blurring of boundaries with romantic/nostalgic “canoe” songs, like “Gliding Down the Waters of the Old Mississippi,” “Where the Lazy Mississippi Flows,” “On Lake Champlain,” “A Little Birch Canoe And You.”

- and, of course, mammy (the reductive image of the black mother as fat, big-bosomed, wearing a bandana, often a servant caring for white children): “Arkansas Blues,” “When It's Sleepy Time Down South”

|

|

|

|

These songs contain a set of stock images – generic images that are barely elaborated in the lyrics. They are so cliched, so stereotyped, that it seems as if pretty much anyone could write them. And pretty much anyone did. There are so

many songs of this type, and their writers often had no connection to

the states or cities they were writing about so nostalgically –

continuing a tradition going back to the northerner Stephen Foster.

Ballard MacDonald, who wrote “(Back Home Again In) Indiana,” was

from Portland, Oregon (he also wrote “On The Mississippi,”

“Beautiful Ohio” – the state song of Ohio – and “By the

Old Ohio Shore”). “On the 'Gin 'Gin 'Ginny Shore” was written by

Edgar Leslie of Stamford, Connecticut and New York City. Hoagy

Carmichael, who wrote the words to “Georgia On My Mind,” was from

Indiana. Spencer Williams, who wrote songs like “Basin Street

Blues” about his hometown of New Orleans, also wrote “Arkansas

Blues” (with fellow New Orleanian Anton Lada) and Tishomingo Blues”

(about Tishomingo, Mississippi).

many songs of this type, and their writers often had no connection to

the states or cities they were writing about so nostalgically –

continuing a tradition going back to the northerner Stephen Foster.

Ballard MacDonald, who wrote “(Back Home Again In) Indiana,” was

from Portland, Oregon (he also wrote “On The Mississippi,”

“Beautiful Ohio” – the state song of Ohio – and “By the

Old Ohio Shore”). “On the 'Gin 'Gin 'Ginny Shore” was written by

Edgar Leslie of Stamford, Connecticut and New York City. Hoagy

Carmichael, who wrote the words to “Georgia On My Mind,” was from

Indiana. Spencer Williams, who wrote songs like “Basin Street

Blues” about his hometown of New Orleans, also wrote “Arkansas

Blues” (with fellow New Orleanian Anton Lada) and Tishomingo Blues”

(about Tishomingo, Mississippi).

The case of “Indiana” (1917) is particularly interesting. While Ballard MacDonald wrote the lyrics, the

music was by James F. Hanley, who actually was from Indiana. However, “Indiana” has musical and lyrical quotes from “On the

Banks of the Wabash, Far Away” (1897), the state song of Indiana, by Terre Haute native Paul Dresser (original Dreiser; his brother was the novelist Theodore Dreiser). And those lyrical quotes include all of the standard motifs – moonlight, sycamores, and the Wabash – which are also quoted in “Wabash Blues” (1921), with lyrics by Dave Ringle from Brooklyn and music by Fred Meinken from Chicago.

Not only were so many writers not from the cities or states they were longing to return to, but neither were the performers. Take Red McKenzie, my musical hero, vocalist and probably the finest jazz musician ever to play the comb. Between the mid-1920s and mid-1930s he recorded “Arkansas Blues,” “Indiana,” “Georgia on My Mind,” and “Way

Down Yonder in New Orleans” – but he in fact was from St. Louis himself.

These songs quickly became infamous for

various reasons. For one thing, there were the racist overtones (or

sometimes explicit racism) of “mammy” songs. The most noteworthy

example may be “When It's Sleepy Time Down South.” The song, full of cringeworthy images of darkies and mammies, was written (incongruously) in 1931 by three black songwriters, and was quickly adopted by Louis Armstrong as his theme song. As Armstrong performed the song continually over the next three decades, he came to be dismissed as an “Uncle Tom” by the African-American community. Beyond their racial elements, the

cliched nature of these songs and their imagery was

subject to attack or ridicule. The stereotyped longing for a simplified, idyllic past that never was of course made for an easy target. The situation was already so bad by

1922 that when the songwriting team of Henry Creamer and Turner

Layton first published their standard “Way Down Yonder in New

Orleans,” they subtitled it “A Southern Song, without A Mammy, A

Mule, Or A Moon.” But the year before they themselves had

published a typical nostalgia song, “Dear Old Southland,” complete with mammy and mule.

In case you, the reader, doubt my

depiction of nostalgia songs as this formulaic, and doubt the images of sheet music covers before your eyes, you need only turn to

the series of manuals from this period for writing popular songs. In his How to Write a Popular Song

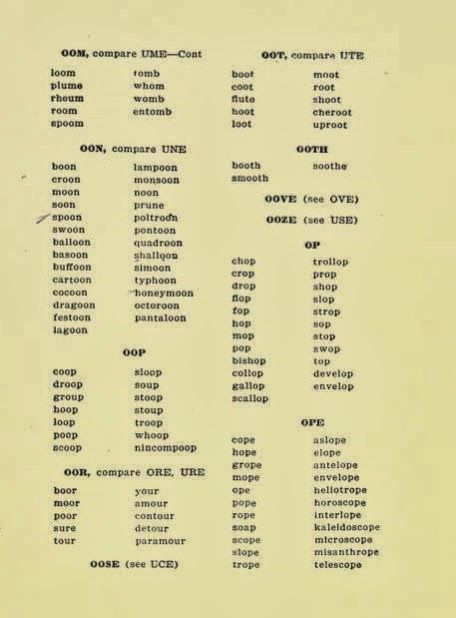

(1906), songwriter Charles K. Harris identifies “home” or

“mother” songs as one popular genre of the day, providing compositional tips, and including a rhyming dictionary at the end

with handy rhymes for words like “moon” (croon, spoon, swoon,

lampoon, octoroon?). Ten years later, E.M. Wickes in Writing the

Popular Song provided more detail about the nature of titles and

lyrics for what he called “rustic ballads”:

The southern states are better fitted to be scenes for rustic ballads than states in other parts of the country. In the first place, the South has always been associated with romance and chivalry; and secondly, the names are more euphonious. Names like Oregon, Nebraska, Michigan, and Dakota suggest adventure, cold, and commerce. . .

Five years ago some may have felt that the South had been exhausted as a source of ballad material, but “The Trail of the Lonesome Pine,” “Kentucky Days,” and “The Tulip and the Rose,” proved that such was not the case, and so long as one can blend a pretty southern love story with a catchy melody he will always have a chance of producing a hit.

|

|

|

|

* * * * *

Now, what does all of this have to do

with country music? To be sure, there is the common theme of

nostalgia, but how do songs churned out by writers

mostly from the north and mostly based in New York City, as part of a contemporary popular music industry, relate to “old-time

music” in the South? “Modern”

country-and-western music had its origins in the late 1920s, with the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers; and, from the beginning, this music was indeed more modern than merely “old-time” tunes. Rodgers in particular mixed traditional country

forms with other influences, including urban ones: he recorded a

series of blues, recorded “Blue Yodel No. 4” with a jazz band,

and recorded “Blue Yodel No. 9” with Louis Armstrong. This trend

in country only intensified with western swing in the 1930s and 1940s

– in terms of instrumentation (such as the adoption of drums as well as brass and reed instruments),

playing style (improvisational, jazz-influences solos, even on the fiddle) – and

also in terms of repertoire. Western swing saw the enthusiastic

adoption of pop standards as well as current pop songs into country music.

A good example is the talented but now largely-forgotten pianist

Smokey Wood. In 1937 his band the Modern Mountaineers

recorded blues songs as well as the nostalgia song “Mississippi Sandman”

(with a “cabin door” and “old familiar faces”). Later in the same year, now under his

own name (as “Smokey Wood and the Woodchips”) he recorded another

nostalgia song, “Moonlight in Oklahoma” (moon; “where dear

ones wait for me, that's where I long to be”) Neither of these is a traditional country song, but new compositions – “Moonlight” credited to Wood himself – written in the same style as Tin Pan Alley hits; but, as if to

emphasize the lineage of nostalgia, at the same session as

“Moonlight” Wood also cut a version of the classic “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny.” Nor was Wood alone. Bob Wills

(the King of Western Swing) and Cliff Bruner recorded

the new pop song “That's What I Like About the South” (with a mammy and trees). Wills also recorded “(Back Home Again in) Indiana,” while both Ocie Stockard and Milton Brown recorded “Wabash

Blues.”

A full tracing of the influence of

these songs in later country calls for a more detailed study. For

now I would like to call attention to one intermediate step in this

development, Merle Haggard's “Okie from Muskogee” (1969). “Okie

from Muskogee” presents us with a set of conflicting traditions and

understandings. Like most of the Tin Pan Alley songwriters discussed

above, Haggard was not from the city or state he sang about: he was

actually from California, although his parents were from Oklahoma.

On the other hand, “Okie” represents something new: the lyrics

are no longer simply nostalgic or wistful, but defiant and

celebratory. There is now a sense of superiority to life in the

city, or to non-traditional ways.

To complicate matters further, Haggard

has given constantly conflicting explanations of how he meant the

song. Sometimes he claimed it was a straightforward celebration of

the country life and rejection of 1960s counterculture; but more

often he claimed it was a satire of the very small-town residents it

appears to celebrate on the surface. However, any possible satirical

interpretation was largely lost on Haggard's country audience. And

in the years since “Okie From Muskogee,” country music has often

run with those sentiments of celebration and defiance. In new

country there is an entire genre of southern pride songs that fall

along a spectrum between nostalgia for rural southern life and

boastfulness about it, to the point of hostility. For instance,

songs like “Chattahoochee” or “Back Where I Come From” depict

some of the same longing or sweet remembrance of southern life as

“Arkansas Blues” or “Moonlight In Oklahoma.” At the other

end of the spectrum are songs like “Redneck Woman” or “Kiss My

Country Ass,” which are a new phenomenon unparalleled in the

nostalgia pop songs.

Like the earlier nostalgia songs from

Tin Pan Alley, the entire spectrum of southern pride songs from

nostalgic to defiant is made up of images. But while there is some

amount of stereotyping in these images – it is nearly obligatory to

mention farms and trucks, celebrate older country music, and/or

express one's faith – the images in many ways are quite different

than the earlier ones. For one thing, there are more of them:

instead of skimming the surface of rural life these songs provide

great detail. For another, those images are much more concrete and

specific. Instead of a few unelaborated motifs we now have a whole

series of themes, ones that are much less reductive. This is not

surprising, since now we also have people from the places about which

they're writing and singing. Alan Jackson, who co-wrote and sang

about the Chattahoochee River of Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, was

from Georgia. Mac McAnally, who wrote and originally recorded “Back

Where I Come From,” was a Mississippian, as he proudly declares in

the song; when Kenny Chesney covered it, he changed “Missisppian”

to “Tennessean” to reflect his own home state.

Personally, I find new country

nostalgia songs to be as overly sentimental as the worst of Tin Pan

Alley songs of a century ago. Meanwhile, the more celebratory songs

come across as off-puttingly hostile, expressing a superiority –

sometimes implied, sometimes explicit – to city/northern life that

is simply a mirror image of the negative coastal view of “flyover

country”. But perhaps we should be thankful that new country

artists have created a whole crop of southern songs without a moon, a

mule, or a mammy.

No comments:

Post a Comment