The Temple Mount in ruins:

This is such an evocative, familiar image of Jerusalem in early Christianity.

The Gospels present Jesus prophesying the future destruction of the Temple. For

early Christian thinkers, the desolate Temple Mount is a crucial representation

of the punishment of

Jews and the triumph of Christianity. The image is so pervasive and

powerful that the idea that Christians left the Mount in ruins in the Byzantine

period is often taken for granted.

Surprisingly, then, there

have been a series of challenges to this idea over the last two centuries. Inspired

by the recent conference Marking

the Sacred: The Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, I decided to

take a brief look at these arguments for Byzantine activity on the Temple

Mount. The following is not meant to be a complete presentation, but a few

important instances that I have encountered in research.

Fergusson’s plan of Jewish,

Christian, and “Mohammedan” buildings on the Temple Mount.

The Temples of the Jews and the Other Buildings in the Haram Area at

Jerusalem (1878).

Fergusson’s theories were influential.

He and the English music writer George Grove, an amateur biblical

archaeologist, promoted them. Both were founding members of the Palestine

Exploration Fund in London in 1865; Grove was the Fund’s original honorary

secretary. In fact, a primary purpose of Charles Warren’s pioneering

excavations for the Fund in Jerusalem – of which we are now marking the 150th anniversary – was to prove Fergusson’s theories. Fergusson provided much of the

funding for the expedition.

West-east section through the Temple Mount at

Robinson’s Arch and the southern wall.

Charles Warren, Plans, elevations,

sections, &c., shewing the results of the excavations at Jerusalem, 1867-70

(1884), pl.

10.

(Click to enlarge.)

2. It was widely believed in the nineteenth century that the Byzantine emperor Justinian (527-565) had built a major church, the famous Nea (New) Church of the Theotokos (Mother of God), on the Temple Mount. The favorite candidate was the Aqsa Mosque: it was suggested that the earliest form of the Aqsa was a basilica, like the Nea, with a cruciform plan. The French scholar Melchior de Vogüé identified the remains of an ancient church in part of the entryway to the mosque: “This church could only be the basilica of Justinian: all the word in agreement on this point.”

Doors of church of Shaqqa (Syria)

and of al-Aqsa Mosque.

Melchior de Vogüé, Le Temple de Jérusalem (1864)

(note that de Vogüé calls al-Aqsa Mosque the “Basilica of Justinian”).

This identification is

contradicted by some basic historical sources, however. The Byzantine historian

Procopius, who provides the most detailed account of the Nea, states that it

was built on the highest hill in the city – which is not the Temple Mount: the

western hill, now called Mt. Zion, is higher. And (as pointed

out by the great French scholar Clermont-Ganneau in 1900) there are textual

sources in the ninth century – a century after the Aqsa Mosque was built – that

indicate the Nea Church was still functioning. Not surprisingly, the identification

of the Nea with the Aqsa Mosque fell out of favor in the twentieth century. Various

alternatives were proposed. Finally, excavations by Nahman Avigad and later

Meir Ben-Dov in and just south of the Old City of Jerusalem (after it was captured by

Israel in 1967), on the eastern slope of Mt. Zion, uncovered

different parts of a massive church that must be the Nea. In a cistern

related to the church Avigad

found an inscription commemorating construction carried out by Justinian. (In

fact, by 1900 Clermont-Ganneau had already

located the Nea on the eastern end of Mt. Zion, using only textual sources.)

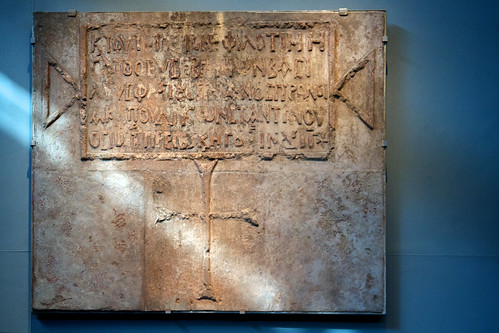

Building inscription from

Nea Church cistern, now in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

(photo by Nick Thompson

via flickr)

3. The idea of Byzantine activity on the Temple Mount has been revived most recently by Gabriel Barkay and Zachi Dvira, co-directors of the Temple Mount Sifting Project: their project has identified coins and many other finds from the Byzantine period. I have previously identified some of the serious problems with this project. Briefly, what is relevant here is that the material – bulldozed on the Haram, dumped by truck in the Kidron Valley, left for about four years, then re-trucked to sifting facilities, where it has sat in an olive grove – cannot be treated as provenanced, as coming from Temple Mount; even if its origin on the Temple Mount/Haram is taken as a given, it is widely believed by experts to have come from Islamic period fill, meaning the dirt (and anything within it) could have been brought to the Temple Mount/Haram from anywhere nearby. Barkay has insisted that the material he is sifting was used on the Mount itself, that the Mount was a “closed box” with no major movement of earth in or out. But he has also qualified these remarks: it was a “closed box” only after the Herodian platform was constructed, and the project has suggested at least in once case that a pre-Roman find was included in fill brought to the Temple Mount at that time; and that the dirt piles from the Kidron could have been contaminated with material not from the Temple Mount. Meanwhile, Meir Ben-Dov has provided persuasive arguments that the elevation of the current Haram al-Sharif is lower than that of the Herodian Temple Mount, meaning that there was major clearance and movement of earth after the time of Herod.

4. Contrary to claims that the Temple Mount has never been excavated, there have been several limited soundings and trial digs on the Haram al-Sharif. The most important of these took place between 1938 and 1942, during the British Mandate, while the Aqsa Mosque was undergoing repairs. Work was observed by several staff members of the Mandate Department of Antiquities. Among the things they observed were trenches dug below the present-day floor of the mosque by the contractors carrying out the repairs; in addition, the Department of Antiquities was also able to dig seven small trenches under the floor.

Example of trench under the

floor of al-Aqsa Mosque

(Mandate Department of Antiquities file SRF 92, photo 21.006)

These trenches helped to clarify the construction history of the mosque. R.W. Hamilton, director of the Mandate Department of Antiquities at the time, later published a monograph on this work (The Structural History of the Aqsa Mosque, 1949). Not included in the publication were several finds predating the mosque, which were only briefly alluded to in Hamilton’s report. These included three sections of mosaic floor, which were first presented by Dvira in at a conference in 2008 and subsequently published in the conference proceedings. Unlike the material recovered by the Temple Mount Sifting Project, these are substantial sections of floor found in situ: they must have been in use on the Temple Mount.

Photographs of mosaic floor

sections

(Mandate Department of Antiquities file SRF 92, photos 20.944, 20.993)

(Click to enlarge.)

(Click to enlarge.)

The only evidence we have

for the floor sections are a small set of photographs from the Mandate Department

files, now put online by the Israel Antiquities Authority (SRF 92). It is difficult to date the floor on

the basis of the photographs, as we have little stratigraphic information. The

only evidence they provide is stylistic: Dvira compares it to two mosaic floors

from Byzantine churches, but also to a wall mosaic from the Dome of the Rock.

Dvira ultimately dismisses the possibility of an Early Islamic date, but the

assumptions behind this dismissal (that there was only one Early Islamic period

building in this area before the Aqsa Mosque, the temporary mosque built by the

caliph ‘Umar; and that we know exactly where this temporary mosque stood) are

questionable. Meanwhile, in a paper just given at the Marking the Sacred

conference, Israeli archaeologists Yuval Baruch and

Ronny Reich suggested that this mosaic floor is Umayyad.